As many of you know, most of the time I’m a responsive photographer. Things happen—often things that I’m not expecting—and I react to them as quickly as I can to take my photograph. Spontaneity is tough to do right, but there’s that old adage: you make your own luck. That works for photography as well as anything in life.

So how do you make your own luck in photography?

Simple answer: set your camera to what you want to happen. Or maybe: set your camera to something unlikely that could happen.

Most people I’ve watched carrying cameras around with them are carrying cameras that are set randomly, most typically set to the last thing that they photographed. That’s fine if the next thing that might happen is the same as the last thing, but if the last photograph you took was last night at the bar or last week at the zoo, what’s the likelihood that your camera is now set properly the next morning when you’re out at the park walking your dog? Right. Zero.

You laugh. At workshops I’m well known to say “check your ISO” from time to time, especially in the morning hours. If your last image was taken in good light, your ISO value is probably too low for good shutter speeds in early morning light. And as the morning rolls on and the light gets better, are you forgetting to lower your ISO back down when you can and get more shutter speed or aperture setting latitude?

It’s always your next image that’s important, not your last photo. You can go back and review your last picture at your leisure any time in the future. But your next image? You only get one chance at it. So how’s your camera set?

It should be set for what’s likely to happen, or what you want to happen, or preferably both.

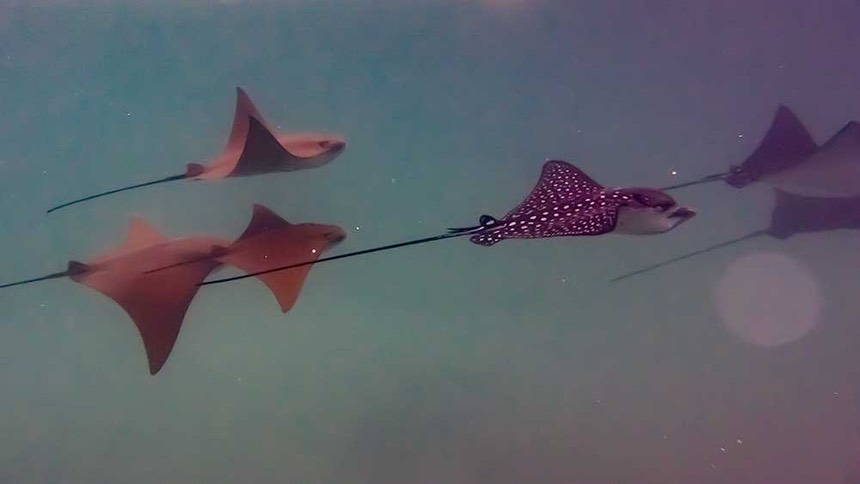

I’ve been in the Galapagos Islands for the past weeks, and as often happens down there, something different pops up on my photography radar every time I visit. This year that seemed to be rays, as in manta rays, sting rays, spotted eagle rays, and all the other darned rays that populate the waters there. There have been trips to the Galapagos where I’ve not seen a ray. But when I’m in the coves and bays, I’m always thinking about them, and my camera is pre-set to capture them. As in:

Now this ray was somewhat expected, though last time I was at this particular location it was sharks and herons that I photographed. So what was on my lens? A circular polarizer, and set to the angle I was pointed at. Why? Because anything in the water I wanted to be able to pull the surface reflections off of. (Hint: Adobe’s Dehaze filter also helps a lot.) I was also concerned about depth of field, as if I really did find something in the water I wanted to photograph, it was likely to be close (the near tip of a ray would be far closer to me than the far tip). I gave up some shutter speed for aperture. Fortunately, most of the things in the water (other than a pelican and a penguin I encountered) didn’t need a lot of shutter speed.

As it turned out, this ray (and his friends) were headed into a dead end in the mangroves. I was pretty sure they were going to come back by me. I decided to photograph them differently the second time: underwater. Fortunately, my Nikon AW1 was also already preset for what I wanted. For those of you who don’t know about this camera, you need to remember one thing: you absolutely must avoid Auto ISO. Nikon’s silly decisions when they made this camera have it almost always picking too slow a shutter speed, no matter what you’re doing! Thus, my AW1 was set to ISO 800, single focus, and a few other settings (including an underwater white balance). Literally, all I did was let the camera I took the first picture with drop to hang from my Blackrapid strap, pick up my AW1 and thrust it into the water alongside the zodiac. I pressed the shutter release once. Here’s what I got:

Note that I didn’t change a single setting. The camera was ready to photograph for what I expected. Thus there was nothing to change. All I had to do was point and take the photo. Fortunately, I pointed well. Because the camera was already set for what I wanted to happen, it photographed well ;~).

But it seems that the rays—all species of them—were everywhere on this trip. Guess the hotter El Nino waters appealed to them. So while I was walking down a beach and someone said “look, rays jumping,” I turned around and photographed this:

The good news was that I was expecting birds, so I was set to a reasonably fast shutter speed and the right focus settings for action already. Sure enough, no sooner did I pick the camera up and put it to my eye I saw another ray jump. Turns out it was the next to the last jump we saw. Had I been fiddling with settings, I wouldn’t have any ray jumping image.

Too many cameras get left at random settings, then stuffed in bags and the bags slung over the shoulder. You head out to where there might be photos and not only is the camera not quickly accessible, but it is set completely wrong for what you might want to do.

Get in the habit of setting your camera for what’s likely to happen next. Or what you want to happen next. That’s the only way you’re going to get photos that pass by you only once.