This blog was published in 2014 and was a day-by-day reveal of the 14 days of one of my workshops.

This mini-blog documents a byThom Photo Workshop in the Galapagos, a two-week cruise on the Letty that occurred in early April 2014. Be sure to read my other Galapagos pages if you’d like to learn more about photography in the Galapagos. I’ve updated them to match my current thinking about how to enjoy the islands.

While this blog was done in 2014, things haven't really changed much since, particularly if you're on one of the smaller yachts.

Just a warning: there will be a lot of photos in this blog and I haven’t tried to reduce their file size from what the students submitted, so it might not be mobile friendly if you’re on a limited data plan. As it is, I’ve had to edit things down, as the students submitted over a thousand very good shots. One thing to note: there’s a bit of inconsistency in processing amongst these images. While I taught some Lightroom and Photoshop techniques on the trip, it wasn’t the focus of the trip, composition and focus were.

Thom Hogan and Tony Medici continue to teach workshops about every other year in the Galapagos. The last filled fast and still had a wait list at the end, so if you’re interested in signing up and want more details, check the workshop page.

To see individual days (pages):

- Day One (3/30) — San Cristobal

- Day Two (3/31) — Genovesa (Tower)

- Day Three (4/1) — North Santa Cruz

- Day Four (4/2) — Isabela

- Day Five (4/3) — Lizard City

- Day Six (4/4) — Rabida & Mangroves

- Day Seven (4/5) — Puerto Ayora

- Boats and Sites and Naturalists

- Day Eight (4/6) — Puerto Moreno

- Day Nine (4/7) — Punta Pitt & Cerro Brujo

- Day Ten (4/8) — The Espanola Horn of Plenty

- Day Eleven (4/9) — Floreana

- Day Twelve (4/10) — Karaoke

- Day Thirteen (4/11) — Sombrero Chino y Bartolome

- Day 14 (4/12) — Lizards and Birds

- Day 15 (4/13) — Hurry Up and Wait Day

- Equipment Used at the Workshop

The full text (in chronological order):

Day One (3/30) — San Cristobal

I’m cheating. Even though yesterday wasn’t an official workshop day (a few of our group were still arriving), I spent a couple of hours yesterday in the Hotel Colon’s excellent conference facilities doing some photographic teaching with the majority of the students. Since I’ve only got a couple more students to get caught up today, I’ll do that on the plane, the bus, the panga, and every chance I get until everyone’s up to speed.

Because I teach some very particular aspects in my approach to photography and use a very specific vocabulary, I need to get everyone bought in and on the same page. No, I’m not going to recap the specific things I teach; come to a workshop if you’re curious ;~). But as you’ll see, we won’t have much time before we hit a very target rich spot, so basically I have only today to get some of my teaching into everyone’s head before the fireworks begin.

This morning we checked out of the hotel and went to the airport for our late morning flight to San Cristobal, where our boat sails from.

It might surprise you that there are now multiple airlines flying to and from the airlines, most notably TAME (the Equadorian military-started airline), and AeroGal (a subsidiary of Avianca). The very first time I went to the islands, there was basically one flight a day. These days there are multiples, and serving two airports (Baltra and San Cristobal). With tourism supposedly* at about 160,000 visitors a year, that implies a need for almost 500 seats a day to the islands, but it’s also common for many of the locals to fly back and forth to the mainland, too. For example, one of naturalists was on the flight with most of the group.

*Why did I write “supposedly”? Because 160k visitors at 16 visitors a group means you need 10,000 group weeks to hit that number. But in terms of boats there are about enough to absorb 100 groups a week, and with 52 weeks in a year that implies a max of about 83,000 visitors using the boats. So either Ecuador is counting Ecuadorians visiting the four cities in the islands, or the number is wrong (or both ;~).

The hour-and-a-half flight is being flown these days mostly by Airbus 319s and 320s (AeroGal), and some older 737s.

Arrival at the San Cristobal airport

The airports on the islands are going through some transition. The new terminal at Baltra has apparently been built since I was there two years ago, and the one on San Cristobal is in progress. The process of landing used to be total chaos, now it’s just near chaos. It used to be that you paid your park fees when you got to the island, and it was worse than customs in some countries with all the people waiting in line, especially when multiple planes landed simultaneously.

Today—at least for San Cristobal—the park fee and forms required are being paid and filled out in advance, so it’s mostly just a line to present them, get them stamped (and your passport stamped with a tortoise if you’d like) and hand you back your exit and souvenir card (don’t lose the exit card; when you leave it’ll cost you US$10 and some extra effort if you do). So things move a lot faster than they used to.

Still, with an Airbus full of folk needing to perform the entry process, there will be a line, and it will take a few minutes to get through this process. Upon exit, you’ll be met by a representative(s) for your boat. No need to claim baggage in San Cristobal, they’ve figured out how to match luggage up to boats and just bring those directly to the boat.

Since I was sitting up front in the plane, as was one of our naturalists, it was just a matter of minutes before I was off the plane and out of the terminal waiting for the rest of our group and introducing them to our two naturalists. Unfortunately, two of our group were amongst the last to get off, so we had to wait one full plane-load to get our group back to together. That said, it’s a far more pleasant process today, faster, and you don’t tend to have situations like what I once encountered, where I was standing outside in the mid-day heat for over an hour waiting to even get to the park entrance procedure.

With the group together, we boarded a bus and made the five-minute drive to the public dock. And that’s when you could begin to tell we were a group of photographers. Sea lions were on the dock, around the dock, near the dock, in the water next to the dock, and everything stopped as shutters started getting clicked. It’s always good to get that first wildlife encounter out of the way quickly.

The panga traffic jam at the docks. This is just for our boat and our two sister boats. Four other boats were loading passengers, too.

Into the pangas (Zodiacs in our boat’s case) and off to our ship for lunch, some preliminary orientation, and of, course, the required fire drill muster and safety test (must be done within 24 hours of embarking, but it makes sense to do it immediately so that people know exactly what they should do in emergencies).

As we made our way on panga to our vessel, we passed my old boat, the M/V byThom. As you can see, you don’t want to leave your boat unattended for any length of time. The animals have a way of taking back territory if you let them.

After a nice buffet lunch, we gave everyone a few minutes to do some unpacking, then at 4pm, we were back in the pangas to the dock, loaded up a bus and went for a half-hour drive up to a volcanic cone filled with a lake at El Junco. The attraction here was frigate birds, though some got caught in photographing other birds:

Wait, I was writing about frigate birds, I think.

The interesting thing about frigate birds is that they are aquaphobic. Unlike many sea birds, they don’t actually dive into the ocean to catch fish. They like to steal from others who’ve done the dirty work ;~). Indeed, frigate birds are a strange bunch: they only nest in bushes or trees, and the only other thing they do is fly plus at this time of year, mate and raise young. They don’t like water because they don’t have the lanolin and other protection on their feathers that many birds do (e.g. the Boobies). They aren’t exactly equipped with long legs like some birds, and the terrain means that if they get to the ground, they often will have a difficult time getting back into the air. I’ve encountered grounded frigate birds that ended up in some dense bushes and had no way to get back into the air without having to pick their way through the bushes on their awkward legs.

Still, all animals need fresh water, and they need to stay clean. And here at our first site, we got to watch frigate birds drop down into the fresh water of collapsed cone (briefly) and get what they needed, and in a few cases, get some much needed cleansing. I watched one young bird get a little too wet, and he then struggled to keep flying after that.

You’ll see frigate birds barely touch water (with their beaks) most of the time. With sea water, they’d only be doing that if they thought there was something they could scoop from the water, such as a fish dropped by another bird. But when they get wet, they start to look a bit disheveled in flight:

Normally, they look much more trim and graceful:

Since this was our first attempts at birds in flight on the trip, and because the conditions weren’t exactly conducive to great shooting, all of us—including me—went through a bit of trial and error and practice this afternoon. That’s sort of as planned. Tomorrow we have one of the best bird sites in the islands to visit, so getting everyone used to what they need to do to get the shots they want was a useful afternoon’s work.

Now for the bizarre side of Thom: I never pass up signs, especially odd or unusual or curiously placed ones. I have this fetish about them: I have to figure out how to use the sign in some visual pun or message of some sort.

Halfway down the trail to the shore edge, which wasn’t all that photographic, we came upon the following sign. Yes, that’s me on the left talking with Drew about what we might do with it, and someone else’s picture of us trying to come up with a picture. Yeah, that’ll work ;~). Foreshadowing: you’re going to see more signs in this blog.

We didn’t have a lot of time with the birds at the lake, as it loses light early and the highland mists also conspired against us. We also have a very long cruise to deal with this evening, and thus need to get away from Puerto Moreno as soon as possible. Indeed, no sooner did we get back on the boat just after sunset, the Captain raised anchor and we were off.

Not a lot of images to write about today, but that will change dramatically tomorrow, our first full day in the Galapagos.

Landings: the docks at Puerto Moreno provide a dry landing, though often you’ll be picking your way through sea lions

Snorkeling: generally no snorkeling on arrival days, as by the time you’ve settled down in the boat you really only have time for one activity

Major New Sightings: sea lion, frigate bird

Day Two (3/31) — Genovesa (Tower)

Sure enough, just before the wake-up call at 6am, I heard the boat slow and the Captain drop anchor. We’re awakening this morning in a bay created from a collapsed volcanic crater, the site of all of today’s activities. We’re going to start our first full day in the islands with a bang: the island of Genovesa has two of the prime visitation sites in the islands, especially this time of year.

First, I need to explain my time references. The Galapagos is technically one hour earlier than the mainland of Ecuador. But our boat and its sister boats do a lot of communication between their Guayaquil offices and the crew, so the boats are kept on mainland time. So even though 6am is usually sunrise on the equator, for us that’s really about an hour before sunrise.

Our goal on this tour is to try to make use of the best photographic light, so we really want to be ashore at the first moment the park service allows (sunrise), and for the afternoon walks, we want to still be ashore right up to sunset so that we can work the best light. And that’s exactly what happened this morning. We hit the dry landing at Prince William steps as early as we could, so much so that the sunrise was still lingering as we topped the steps. We split into two groups, one with my assistant Tony and naturalist Cecibel, one with me and naturalist Billy (I’ll introduce you to them later). I let Tony’s group get ahead of us and out of sight, so basically we had the best possible scenario: two small independent groups that didn’t see each other, and thus, weren't competing to get the right angles for shots.

Genovesa is bird city. There’s not a huge variety of species, just a huge number of birds. We’ve got two types of boobies (Red in the bushes, Nazca on the ground), frigate birds, an owl, and a handful of other common birds, including doves, mockingbirds (that don’t mock anything!), storm petrols, and more.

The frigate birds are in full mating season, so as females fly overhead the males are blowing up their red pouches showing the ladies a little wing with their best singing.

One thing you’re going to note is that backgrounds can be quite busy (bushes, rocks, other birds, you name it). So you either have to minimize them or use them. David’s used the background in his shot; I’ve minimized it.

Once a frigate bird has his mate, they’ll stay together on the nest until the young are hatched, then take turns at feeding.

The boobies are also mostly paired up right now, so we’re constantly hearing the males whistling and the females honking. As with many birds, there’s a lot of beak-to-beak action in the mating rituals, and we were seeing it all pretty much from step one on the island. Foreshadowing: you’re going to get tired of birds mating ;~)

The highlight of the morning was an owl that had caught a storm petrol and flew over the first group to go sit eating it in full view of the group. This isn’t the greatest shot of him, as it’s a small bird that landed quite a distance from us. Here he is doing his best DeNiro imitation (“You Talkin’ to me?”):

The group in front of mine (Tony’s) saw him land with his catch:

Or maybe the highlight was the two frigate birds actually mating.

Or maybe it was some bird fights. Or maybe… well, I’m sure everyone had their own highlight. When one frigate bird has something (nest material or food) in its beak, others will come to try to get it away:

One thing I notice that the frigate birds sometimes do is that they will suddenly go from flight position to some sort of wind-aided grooming position:

Not only does it look awkward, but I don’t see how they keep from dropping to the ground when they do this. Maybe it’s helium in that big red bag instead of just air (just kidding).

One key teaching point for the morning was “eye level.” The natural tendency is to walk up to a bird on the ground and shoot down at it. Or to point up at a bird flying overhead. Sure, take those shots. But shots are much more involving and engaging to the viewer when they feel like they’re eye-to-eye with the person or animal. Hopefully you’ll see that in the illustrations in this blog. So, a tip to shooting children: get down on their level so that the camera is eye level, not standing adult level. Since we have birds on the ground here, that means kneeling, or sitting, or shooting in the prone position. And, of course, the ground is volcanic rock, so it’s hard, jagged, and uncomfortable. It’s a good idea to bring kneepads or a small cushion to help keep your body from getting all cut up and to make such low-level shooting more comfortable.

Eye level works even when you’re shooting someone’s back:

I see what David wanted to show here: while the frigate bird looks black, it actually has a set of green feathers on its upper back.

After we returned to the boat, it was time to get snorkel gear sorted out and off for the first snorkeling of the trip. Besides the usual fish you’d expect to see, the first snorkel also gave everyone their first views of the Galapagos shark and the Hammerhead shark. Now that’s what I call an introduction to the underwater world:

Yes, we’re getting that close to the sharks. Most of us were using wide angle lenses on our AW1’s (28mm equivalent), so keep that in mind as you see underwater shots from the workshop. Just as access to animals is great on the islands, it’s also great under the water.

In the afternoon, we had a wet landing at Darwin’s Landing. Ironically, Darwin apparently never landed there. Within a few feet of the landing spot:

My image of the same juvenile squawking for food:

Note that I’m absolutely at eye level here. I’ve got other images from the sequence of the parent feeding this juvenile, but I picked this one to show just what I mean by “eye level.”

Tony, as usual, starting collecting “new birds” for his collection:

Here’s another of those frigate bird males trying to land a woman.

The wet landing area here is also a site where we often are greeted by sea lions:

Masood, Margaret, Ceci one of our Naturalists, Carol and Drew, Thom, and Joy at the end of the day. Note the smiles and the long shadows. Photographers do it with the sun near the horizon. Also, this shows you how small a group we can be with our use of two naturalists and two photography teachers. Basically, when we were on the serious visitation sites, we were in groups of 8 or 9 total. Most tours in the Galapagos put as many as 17 people down in one group (16 guests and 1 naturalist). Smaller groups are more flexible in terms of moving slow or fast as need be, plus the student to naturalist/teacher ratio was 6:1 or 7:1. Easier to ask questions and get answers, easier to find a shot without others trying to nudge you out of the way. Just a better way to experience the islands, which is why I do it this way. And yes, I’m in orange today instead of my usual more neutral colors so that it’s easier for the students to figure out where I am if they need to ask me something. Even though we’re in a small group and are supposed to stay in a group, we do tend to spread out a tiny bit at times as people get stuck on different photos. Note something else: wide-brimmed hats and no sunglasses (though there were times we used them). Keep the eyes shaded, but see the world as it is, not as your ophthalmologist’s filters think it is. Using sunglasses is one of the number one reasons why people start cranking up contrast and saturation and other camera settings: they’re trying to match what the sunglasses see. The problem with that is that once those things are in the image files, they’re difficult to take out or adjust with subtlety (at least for 8-bit JPEGs; most of us are shooting raw, but when you crank up the camera settings shooting raw the histograms and highlight information starts lying to you about the actual raw data). They also sometimes have problems seeing camera LCDs and EVFs if the polarizations align.

As light wained, I decided to go for something completely different, and started dragging my shutter speed:

Hmm. Not my best effort, but it’s day one and I’m a bit out of practice. It is “broody,” and you’ll remember that I like broody images (more foreshadowing). Just as a note, broody rarely works in small form displays like this. It works far better with large prints. On days like this where I’ve managed to get plenty of good “normal” shots I’ll try some alternative techniques like dragging the shutter and panning with moving subjects. I highly encourage experimentation. When experiments don’t work, that’s when you learn the most, by the way. One of the things I learned by dragging shutters this afternoon is that it works better on boobies than frigate birds. Why? Because most of the time the boobies don’t have any up/down motion to their body when they’re flying, while the frigate birds do. Since I’m trying to keep the head perfectly steady in the frame, any up/down motion just makes the bird’s head and body less distinct. There are moments when the frigate bird is steady like a booby, but I need to work harder at finding and exploiting them. So: failed experiment, successful learning.

At the end of the day everyone is excited, exhausted, happy, and now on their laptops plowing through hundreds of images they’ve already taken. It’s been a long day, but a productive one. Tomorrow’s wake up call? Yep, an hour before sunrise again.

Landings: Prince William Steps are a dry landing with some potentially slippery rocks on the first step or two; Darwin Bay Landing is a wet landing (usually in calm and shallow waters, though with jagged rocks/shells in the sand)

Snorkeling: typically done off the panga along one of the rocky edges in the bay as we did, but can also be done from Darwin Landing beach

Major New Sightings: Galapagos and Hammerhead Shark, Red-footed and Nazca Boobies, Terns, Owl, Lava Gull

Day Three (4/1) — North Santa Cruz

Another long cruise overnight brought us to the Northern side of Santa Cruz to Playa Las Bachas. Again we were able to get right onto shore at first light.

The beach here was in pristine form when we hit it, and we could clearly see turtle tracks up to the top of the shore dunes, where the females dig holes and lay their eggs. We were hoping that we might find a tardy turtle who didn’t get her chore done deep in the night, but unfortunately we weren’t lucky.

Still, we had an enjoyable morning walk at Las Bachas, visiting two lagoons, each with a single flamingo and perhaps a half dozen marine iguanas, some doing their glamour shot poses for us (above). Plus we found a mother Lava Gull and her two chicks nicely camouflaged in the rocks. Indeed, so well camouflaged that even if you pointed the spot out to someone, it took them awhile to actually see the chicks. Generally, most people didn’t see them until they moved.

That’s probably a good thing, as Lava Gulls are now endangered and less than a thousand of the species remain here on the island.

As usual, the shoreline provided plenty of interest today:

After our morning walk, it was on to Baltra, where we stopped to pick up fuel for the boat. Surprisingly, very few boats were in the harbor, which means that we’re probably in a little gap of boats (most National Geographic cruises start a day earlier than we did). So while the Letty (which we’re on), Flamingo I, and Eric owned by Ecoventura all started off together, we’ve seen very few other boats so far. I hope that is going to remain mostly the case, but we haven’t hit any of the most popular sites yet. This week we’re on what I’d call the “far reach” tour, as most our visitation sites in this first part of the workshop are well away from the two airports and the primary circuit, and especially far from the Letty’s home port on San Cristobal.

But today, we’re never more than an hour-and-a-half boat ride from the bigger airport, so I’m wondering where the other boats are. Perhaps we got lucky and got two visitation sites that the others didn’t.

After lunch and the refuel, we moved the boat to Cerro Dragon and some went for a mostly uneventful afternoon snorkel (don’t worry, they’ll get eventful). After the snorkel, we disembarked for the land to see:

Yes, another lone flamingo. Guess they’re all ignoring each other right now and setting up in separate ponds. David did a great job of catching the stray feather in his shot. Tony’s got great leg position and the beak drips timed nicely. So one thing you might realize that I was talking about during the workshop was “timing.” We’re looking for something besides that glamour pose I started today’s post with: we want to see animal behavior, and we want to capture just the right moment when we can show something besides just a basic portrait of the animal.

Cerro Dragon has a bit of history. It’s one of the few places on the big island of Santa Cruz that has native land iguanas present. The problem is that there were feral dogs in the area, threatening the lizard population. The park service moved the iguanas to a “penned” area elsewhere on the island, even moving soil from the Cerro Dragon area so that the iguana nests could be in their natural environment. The dogs have since been removed, and in 1990 the park began returning iguanas back to Cerro Dragon. The animals are still a bit skittish, though, and the park service has to continue monitoring feral animals in the area, particularly cats and donkeys.

The good news, of course, is that iguanas are one of the two very successful breeding and repopulation successes Charles Darwin Station and its researchers have accomplished over the years. Cerro Dragon had no iguanas when I first visited the islands. Now it does again.

You’re probably a bit surprised at the photos you’re seeing so far: not exactly what you expected, right? Part of that is our itinerary, which is very bird oriented up front. Don’t worry, you’ll see more and more diversity, just as we did. In the meantime, it’s worth looking at a few of the other things we’re encountering:

We originally decided start image reviews tonight, but that was cut short by an announcement from the Captain that there had been a 8.2 earthquake in Chile and the Islands were now under a tsunami warning. While the ocean is very deep outside the islands, the inner area is a relatively shallow plate, and that’s where tsunamis raise their ugly heads and cause destructive. Unfortunately, we’re right in the middle of that shallow area at the moment. That meant that we are going to rush to deep water (500 foot or higher) instead of our intended route and are going to get bounced around a bit in more open ocean. The Equadorian Navy asked that all boats pull out of port and get to 200 feet deep water, so we’re playing it even more safe than suggested. Still everyone went to bed wondering what was actually going to happen that night. Would we get a “big wave” or not?

Landings: Las Bachos and Cerro Dragon are both wet landings, with fairly quick drop offs into deep water; Cerro Dragon is a rocky beach

Snorkeling: done off the beach or panga

Major New Sightings: flamingo, new finches, baby finches

Day Four (4/2) — Isabela

Yesterday I left you with a mystery: what would happen to our little crew when the tsunami hit? Answer: it didn’t. At about the right estimated time a tsunami should have arrived here at the equator we encountered a change in the sea from calm to very choppy, and there was one point were it felt like we on top of a small surge. But that was it. So, sorry folk, Thom’s still with you.

Unfortunately, the big diversion out to sea on a night when we already had a long cruise ahead of us meant that we arrived at Punta Vicente Roca late in the morning. Our activities today started with a panga ride along the cliffs, followed by a snorkel in the same area.

During lunch, we moved the boat down to Urbina Bay, where we once again found ourselves pretty much the only ones at our visitation site (virtually none of the boats seem to be going out as early as we are, or stay out as late; everyone else was just finishing up as we came ashore). The nice things about being last at the site is that we can spread the two groups out and take our time. And time we took, as we immediately hit a Giant Tortoise feeding on small apples form an endemic tree. A few steps down the path, and we had a second Giant Tortoise, and a few steps beyond that we started seeing the land iguanas, and literally right in our path.

I’ve given you the full view here. We’re on a modest path, and the animals sometimes use the path as well. That’s a large land iguana mid-photo in the path. Sometimes we catch the animals crossing the paths (below), sometimes they’re just off the paths.

As I noted, we also got our first peek at tortoises today (soon to appear on the GoPro video site, apparently; just tell everyone you were shooting slow-motion).

Often, when you’re standing there photographing something, it may walk right over to you. While this isn’t one of the bigger tortoises, be aware that if a giant tortoise wants to go somewhere and you’re in the way, they don’t stop. They’re not used to anything being able to stop them, and even smaller ones like this may outweigh you.

The very first time I visited Urbina Bay in 1990, the iguanas were skittish because there was still some feral activity, and the tortoises tended to be deep in the brush. But the park service appears to have eradicated the non-endemic predators, and now the land iguanas couldn’t care less about people. Indeed, you really have to watch where you put your feet, as it’s easy to step on a tail sticking into the trail if you’re not paying attention.

Landings: Urbina Bay is a wet landing, again with a fast drop off into deeper waters; also, this landing is well known for big waves at the landing site

Snorkeling: done off the panga at Punta Vicente Roca, can be choppy

Major New Sightings: Blue-footed Booby, Turtles, land iguanas, giant Tortoise, Galapagos Hawk, penguin

Day Five (4/3) — Lizard City

Since we anchored at nearby Punta Espinoza overnight, an early wake-up and breakfast got us onshore at the earliest possible time, plus there were no other boats anchored with us, so we had the site to ourselves for quite some time this morning. Indeed, this was one our longest walks to date, time wise. Punta Espinoza is the only visitation site on Fernandina, and the island has no introduced mammals, which is one reason why you see such a huge colony of iguanas here: basically it’s only food sources that constrain them. This particular area was formed in the 1800’s by volcanic activity that caused an uprising, and Fernandina is the island with the most recent volcanic activity (a huge eruption in 1968, the most recent in 1995).

The attraction here is instantly visible: marine iguanas everywhere. It’s almost impossible to not step on a lizard tail there are so many of them. It may be difficult to tell from the wide angle shot, above, but those black objects are not lava (though they’re on the lava): they’re literally thousands of marine iguanas. And these iguanas all had first light on them. At this time in the morning, the lizards are just trying to warm their bodies to get ready for their swim for food. So while we have thousands of iguanas to try to figure out how to compose, at least they’re not moving around (much).

It took us almost three hours to do what couldn’t have been more than a mile worth of walking (the full trail is about 2000m, but we didn’t do it all). With no other groups on land, we had plenty of time to work on framing pile after pile of iguanas. We also had some more interesting bits, such as one Sally Lightfoot crab snacking on another Sally Lightfoot crab. If you look carefully to see everything that’s around you, sometimes you spot little anomalies like that. Plus there’s always the occasional male dominance fight with the iguanas (hint: December would probably be peak season for fighting males).

You really have to keep your eyes open, despite all those distracting iguanas. Doug managed to find someone having breakfast:

This brings up the tension point about places that are so target rich like this one. You have a choice of the bird in the viewfinder, or two in the next bush. It’s a tricky dynamic. Personally, I think you should keep with the bird in the viewfinder (or whatever you’re shooting). The only reasons to move on are: (1) you’ve optimized that shot (and be honest with yourself on that) and aren’t likely to get better; or (2) you haven’t optimized that shot and need to work it some more to get the best possible shot. Sometimes with animals or light you’re playing a waiting game, too. You’re waiting for the bird to take off, or the lizard to shoot sea salt out its nostrils, etc. So there’s always a judgment call involved. And yes, in places like the Galapagos if you move ten feet you might be treated to something better.

But what I’ve found is that far too many people—including myself sometimes—are too quick to dismiss what they’re doing for fear of missing something else. I’m pretty sure that even just five days in, everyone’s looking at everyone else’s images and wondering why they didn’t see something. Well, they were working on something else, that’s why! There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that. If you let yourself get into image envy you’re selling yourself short. Find a shot and take the best possible version of it you can; yours may be the shot that others wished they had gotten ;~).

This tension is one of the reasons why many of us pros return to the same place over and over. Sure, we didn’t get the bat being eaten by the snake shot this trip, but maybe next time.

Note that on most one-week Galapagos tours the tension is almost always broken by the guides forcing you to move on as a 16-person group. Being the one serious photographer in a large group that includes more casual visitors is almost guaranteed to be frustrating, as you’ll be dragged forward as the attention spans of the rest of the group wane. So far in this trip not a single other group has been on any visitation site as long as we have, and I expect that to continue, as we’re working very slowly through the landscape.

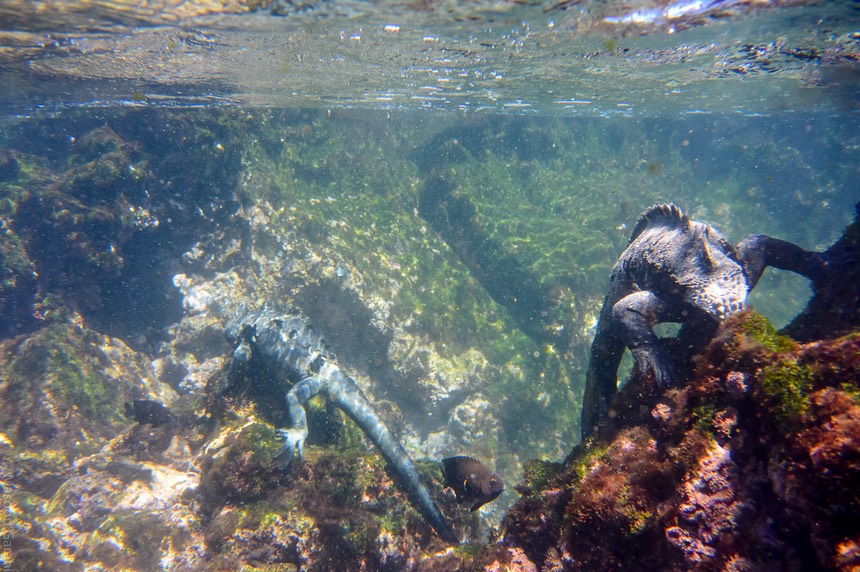

As we finally began to get back on the pangas, many of the lizards were now entering the water. Which is perfect, because as soon as we were back at the boat we changed to snorkeling gear and went right out to find where they are eating underwater. And that snorkel turned into a real winning swim:

Yes, those are lizards swimming and eating under water (and one human).

An aside: many of us were using Nikon 1’s underwater (including at least one J1 in an UW housing, but mostly AW1s). As you probably noticed, this site probably now has more underwater shots with those cameras than Nikon’s, and very authentic ones. The AW1 turned out to be a near perfect snorkeling camera. The other popular underwater camera was the GoPro, which also worked well:

During lunch we crossed back over to Isabela to Tagus Cove on Isabela, where we started with another snorkel (the photos above starting with Tony’s shot of the GoPro user). Then late in the afternoon we did a landscape walk up to a collapsed cinder cone. Tagus Cove itself is a collapsed cone, with the center actually in Darwin Lake (bottom water, below). Darwin Lake is salt water and sustains no wildlife.

As always, if you look carefully, you’ll find animals while you’re hiking:

Landings: Punta Espinoza is a dry landing that has a small wade through a mangrove pond; Tagus Cove is also a dry landing, though the rocks can be slippery with sea lions in the way

Snorkeling: Tagus Cove snorkeling is done via panga generally along the rocky edges of the cove, very sheltered

Major New Sightings: masses of marine iguanas, iguanas eating underwater, rays, flightless cormorant

Day Six (4/4) — Rabida & Mangroves

After another choppy night on the water as we moved through a storm system (it’s the end of the wet season here), we arrived at yet another of the Galapagos’ unique features: a red sand beach at Rabida.

So why’s the beach red? It has to do with the metallic content of the volcanic activity. If you were able to visit all the beaches in the Galapagos you’d find white, black, green, and red sand. Each of those variations is due to the metal and mineral contents in the lava that formed the island.

As we beached, we were met by a sea lion pup and some oystercatchers.

We also had some feisty mockingbirds that were flitting all about us:

Unfortunately, those were pretty much the highlights of the walk, as we only saw lava lizards and a few repeats of smaller birds we’d photographed before. Plus a lot of cactus and rocks. Nevertheless, it’s always good to stretch the legs, and the beach itself is a bit of an attraction.

Jari did manage to find an upside down marine iguana nibbling on some algae revealed by low tide, but the lizard didn’t hang on for long:

As usual, we did some snorkeling. I’m not so great at identifying fish, so I’ll just say we saw some new ones plus an old friend.

Perhaps as a reward for a not-too-dramatic morning, as we pulled away from the beach we were met by a huge pod of dolphins, which spent a few minutes riding our bow waves and jumping alongside us as we headed to our next destination.

We spent the late afternoon paddling through the mangroves at Black Turtle Cove on the North side of Santa Cruz.

Besides the pelicans dive bombing for fish at the entrance to the cove, we had a wealth of sightings once inside the calm waters of the labyrinth. First up were baby Black Tipped Sharks.

Next was a Lava Heron fishing in nice light.

This was followed by a few sea turtle heads popping up. But the big thrill was seeing a school of Golden Spotted Rays as we were coming out of the cove at sunset. Really tough to photograph, but a real joy to watch as they gently navigated around our two pangas to head out to sea. Which of course, we did ourselves just as soon as the last rays of the day were gone.

Landings: Rabida is a wet landing, generally very calm, but with a fast drop off that can be tricky in rough water; Black Turtle Cove is a panga-only ride into very calm waters, though visibility in the water can be impaired at some times of the year

New Significant Sightings: Oystercatcher, Dolphins, Golden Spotted Rays

Day Seven (4/5) — Puerto Ayora

Our choppiest night navigation yet took us to Puerto Ayora, the largest of the three towns in the islands. The first time I came here, the population was less than 1000. The last census apparently showed 21,000 permanent residents, and the differences between 1990 and 2014 are deep and broad. This sleepy little town is no longer sleepy. About the third time I came to the Galapagos my guide took me to a disco that had just opened. Now there are at least three night clubs with dancing. There’s public WiFi available at the pier. The roads are (mostly) paved, and a new electrical system is being put in from town to the highlands.

Once again we set out early, arriving at the Charles Darwin Station before anyone else, which allowed us to linger at the various exhibits in ways that are impossible once the big ships—there’s a National Geographic ship in port—start spewing passengers. Oddly, one of the big male tortoises was trying to climb onto another one, which was amusing to watch. I mean, once you get on top, then what are you going to do?

We also managed to see a few tortoise fights. With the saddleback tortoises, the fight is simple: stick your neck all the way out and see how high you can get your head. The one who’s looking down at the other wins. The fights rarely—but sometimes—go further, which would be the biting stage. But the tortoises generally only take one look at their opponent’s neck and declare a victor.

The Darwin Station has now bred and reintroduced over 2000 giant tortoises on a number of islands, which is quite a breeding success. But it’s not just tortoises they work with, they also are working with land iguanas in a similar fashion. If you go back to Darwin’s days here, you find that he wrote about land iguanas on islands that today don’t have populations of them.

From the station we met a bus to take us up to the highlands. Our first two stops were geological: the Twins, a set of large sinkholes, and a lava tube. It’s easy to forget that these islands are relatively young, and that they don’t really have nearby land to have wind blow dirt onto them. While there’s plenty of vegetation around, it’s a thin layer on top of volcanic deposits. Mangroves are often the first plant life settler in such situations, and we see them everywhere on the islands.

Our main destination in the highlands was one of the farms. Yes, there is private land on some of these islands, the largest amount here on Santa Cruz. However, the giant tortoises are protected even if they cross over into private land. A long time ago some of the farmers saw ways to encourage tortoises to remain in parts of their acreage (hint: build ponds and mud holes) and cater to the tourism business. These operations are one place where you can see the animals close up, in quantity, and in something akin to the territory you’d have seen them in had you arrived before Darwin (one difference: introduced grasses and plants that wouldn’t have been in these areas, though the tortoises still would have been).

Just look for a mud hole and you’re likely to find a tortoise. If not (and even if you do, just be patient):

Yep, they get quite muddy (check out the left side of the above tortoise’s shell after he came out of the pond).

It’s always interesting watching people’s reactions to seeing the tortoises on Santa Cruz (at the research station and in the highlands). If your boat hasn’t made many stops yet and this is the first place you see land iguanas and tortoises, the excitement will be palpable, and the group tends to spend lots of time lingering on the animals. On the other hand, if you’ve been cruising for most of a week as we have, and have seen these animals in their natural habitat, the most interesting thing about a day like today is that you can find someplace to sell you ice cream ;~).

We came back to the boat for lunch and a nap, then in the late afternoon those that wanted to headed into town to souvenir shop. Today and tomorrow are our “lower key” days in the middle of the trip, where our schedule is a little more relaxed and we’re around a few more people from other boats. Come Monday, we’ll be back at places where we’ll be doing three and four activities a day and concentrating on getting better photographs. This weekend, though, is a little bit more like vacation time than serious photography time.

Part of a local artist’s elaborate wall tile mosaic, which extends dozens of yards. Just look for the tile arch on the way to or from the Darwin Station from town, head through it.

Landings: Both the Darwin Station area and the main town have piers that are dry landings. At Darwin Station, sometimes you have a bit of rough water and marine iguanas or sea lions on the dock to deal with. At the main town dock, the main problem is human congestion. Puerto Ayora actually now has designated docks for various boats/groups, and a complex water taxi system, as well.

Significant New Sightings: People! Lots of them. Cars, buses, places that sell ice cream. At Darwin Station you can usually see sub-species that you can’t see on most tours, as it has breeding populations for both tortoises and iguanas for islands and sites that currently don’t have them available to tourism.

Boats and Sites and Naturalists

At present, there are 93 boats registered with the park service that are hosting trips through the Galapagos National Park. Of those, most only carry 16 passengers, or, as in the case of the boat we’re on, the Letty, a maximum of two groups of 10 passengers.

A handful of large capacity cruise-type ships prowl the waters, most notably the National Geographic ships. These large vessels start at 48 passengers and go up to 100 passengers. Currently that includes the Eclipse, Galapagos Explorer II, Galapagos Legend, La Pinta, National Geographic Endeavor, National Geographic Islander, Santa Cruz, and the Xpedition. Not all of these big boats tend to be working the waters at the same time; some do cruises elsewhere, as well.

Some boats are shorter, multi-floored motor-only boats (the Letty is one), others are motor sailors. Next year’s trip will be on the Mary Anne, a 216-foot three masted sailor that is really set up to handle 32 people, but only books 16. [Sponsored link: Wilderness Travel uses the Mary Anne for most of their trips. Tell ‘em Thom sent you and I might get a brownie next time I visit the offices. ;~]

So some boats are a little tighter and cozy, while others are big enough that you can find space where others can’t find you. The difference in boats makes more of an impact if you’re, say, a family of five just out to vacation together. The smaller boats will have in you in close quarters with others. For a workshop, though, it’s not as important, as long as everyone is participating in the workshop: cozy actually means more interacts photographically. You can learn from other students as well as instructors.

The big National Geographic boats and the like are more like “cruises.” Dining for 16 is a lot different than dining for 48 or more. The NG boats tend to have multiple experts who give presentations on various scientific and historical aspects of the islands.

Each boat has assigned visitation sites by the park service on what is called a tourism patent. While there are about 74 active land sites, some additional sites are closed to let animals get some rest from the tourists or for feral animal removal, while others have tougher restrictions on the number of boats that can be there at a time. The park service is trying to balance the tourism load across the park, while still providing enough access to tourism so that you can see a wide variety of animals, geology, and plant life. 66 boats do the basic cruise we did. There are also 9 boats doing daily tours, 23 boats doing daily dive tours, and 7 boats doing multi-day dive tours. Each boat has a fixed schedule, which you can see on this page.

If you want to see the visitation site details, go to this National Park page and click on the Visitor Sites Guide in the middle of the page.

Most boats are running one week cycles for what is a two week itinerary. So they pick up their passengers from one of the two airports on, say, a Saturday and return them to that airport the following Saturday. If you’re on a slower boat, that may mean that you don’t get out to the extremes (such as Genovesa). Even if you’re on a faster boat, your one-week cruise will consist of a small subset of what the Galapagos has to offer. The tour company might refer to that subset as “Northern Islands” or “Western Islands” or “Central Islands” or “Southern Islands”, and so on, which gives you a general flavor of your boat’s destinations for the week.

My workshop is two weeks for a reason: it allows us to hit pretty much everything people would want to see, and it maximizes what the boat you’re on can do (i.e. you’re seeing both halves of their two-week cruise schedule). In total, we hit about half what’s available to non-divers. Because of park limitations on usage, the odd island out on our trip is Santa Fe, but we’re touching pretty much all the other places I’d want to be when photographing in the islands.

Most of the boat crews run on eight week working schedules: eight weeks on, four weeks off. On our crew we’ve got a mix of those from San Cristobal, Puerto Ayora, Guayaquil, and Quito. You can always tell when we’re near an island with a cellular signal: the crew tries to squeeze in a few minutes of talk with their family. While eight weeks away from home is a tough life, it’s also one that pays relatively well, especially when the tourists tip well. It would be hard for some of the crew to support their families as well as they do if they had to take jobs back in Guayaquil.

Obviously, the ones that live on the islands get chances to pop into town during the cruises. For instance, Ronald, our waiter and bartender, went into town to spend some family time this afternoon (I’m writing this at Puerto Ayora). But for those whose families are back on the mainland, they have to rely upon phone contact only, and intermittent contact at that.

Naturalists have to train at many things and pass tests to be selected from the best candidates, though there is an active program to help those that grew up on the islands to study for becoming a naturalist. At the moment there are about 400 certified naturalists. If you’re doing the math (400 * 16 = 6400 tourists/week, which would put the tourism at over 330,000 a year, more than twice what it likely is) obviously they aren’t all working all the time. There’s great competition to get on the best boats and have the best schedules.

Cecibel and Billy are our two naturalists, both Class III, I believe (there are three classes, with III being the highest):

Both Ceci and Billy are long term veterans in the Galapagos, with over two dozen years of naturalist guiding between them. Besides their constant smiles—who wouldn’t be smiling with this job?—they were great ambassadors for the islands: full of useful and interesting knowledge, gentle in spirit and ever helpful, proud stewards of their park, and as it turned out, really great snorkelers.

You can find out more about the Naturalist Guide program on this park service page. Guides fill out reports for every trip, and evaluate one another as well as incidents or problems that they spotted during the trip. They’re really the daily eyes and ears of the park service in terms of monitoring the health and quality of each of the visitation sites.

To learn about current research at Charles Darwin Station or to donate to help further that research, visit the Charles Darwin Foundation page.

Yes, this was a little break from the animals, and tomorrow will be another soft day as we are in port to restock supplies and get the boat ready for week two. But trust me, week two will have even more of the photography that I hope you enjoyed in week one, as we visit the Southern and Eastern islands in the archipelago.

Day Eight (4/6) — Puerto Moreno

We’re back at our starting point, Puerto Moreno, because the boat needs to get restocked and readied for our second week of cruising, this time through the Southern Islands of the Galapagos. If we had been a typical one-week cruise, we’d have disembarked after breakfast this morning and driven to the airport to return to the mainland. Instead, we’re having a low key day as we get for another spin around the islands.

The blog entry will be a little short today because I’m remaining on the boat and doing some other much-needed writing. I don’t want to get home and have two-weeks of no writing for books and the main sites behind me. I also spent part of the morning washing clothes, cleaning gear, and rearranging my cabin to get rid of the week’s worth of clutter I had accumulated. No photography for me today.

A small group of the workshop participants went out to a beach about an hour’s drive from town to spend the morning.

Even fences won’t keep a sea lion off your boat (and getting them back off becomes harder, too).

After lunch, most of the group went for either a snorkel or a panga ride looking for shorebirds. We did do a short image review session with everyone after lunch, but that’s the extent of my workshop work today.

So, a slow Sunday. There will be more to report tomorrow, as we head up the coast to two locations that should be rewarding. And then later in the week we hit two of my favorite places in the islands.

One thing before closing the document and moving on to other work: one week in the Galapagos is too brief, in my opinion. It’ll feel a little whirlwind, and you often don’t get second chances at a lot of the animals due to the way they’re distributed on the islands and your fixed itinerary. On the other hand, two weeks is a bit much to be deeply intense into the photography side. So if you come to the islands for a two-week trip, find a day in the middle where you can just relax and unwind. It’ll usually come right at the 7 day mark with the boat in port, so you can even make it a “stroll around town” day if you want. Put the camera away as I did today and give the photographic mind a bit of subconscious time to think. That way when you start hitting those more exotic animals a second time in the second week, your brain will be ready to help you improve your shots.

Now watch what’s going to happen: the shots from the second week will all go downhill on me ;~). I hope not. But time will tell. Still, that’s my advice: relax in the middle of a two-week Galapagos trip.

Day Nine (4/7) — Punta Pitt & Cerro Brujo

This morning’s location is Punta Pitt, at the Northern end of San Cristobal. This is a location I visited 20 years ago, but was closed afterward for almost 15 years.

Despite the land in the islands being 97% National Park, that doesn’t mean that all areas are National Park pristine. Punta Pitt used to be one of the places in the park where you could see all three booby species at the same time. High up on the bluffs at the very tip of the island the terrain was just right for all three of the birds. Nazca’s had some nice flat ground, Red-Footed had enough bushes to nest in, and the Blue-Footed tended to nest at the cliff edge.

Unfortunately, feral animals got into the mix. In particular, feral rats and goats. The boobys were all impacted by this, and obviously moved their nests. Eventually the park service eradicated the feral animals from the area, but you still wouldn’t want humans wandering through until the bobbys had fully reestablished the area. If humans were present, the boobys might not return. Thus, the park kept Punta Pitt closed for 15 years. It’s only recently re-opened.

The good news is that the feral problem is no longer present. The bad news is that the bird population in the area is now relatively minimal. After hiking up the steep trail to the top of Punta Pitt, we found only a few Red-footed boobys in the area where I had seen hundreds before, and not many of them in good light (the juveniles, you might have noted above, were in poor light). In other words, the area hasn’t fully recovered, which is a shame, because the bluffs are particularly scenic. Yet without hundreds of bird nests, it really seems like something is missing.

I mentioned I love trying to play with signs photographically. Joy and I did different things with basically the same sign today:

Joy’s interpretation is “no humans,” while mine is “don’t stand with your hands at your sides.”

After our hike, the snorkel in the area produced the opposite result: plenty of sea lions who wanted to play with the swimmers, and plenty of additional underwater wildlife to keep everyone busy.

In the afternoon we pulled into Cerro Brujo, a long white-sand beach area, where we enjoyed some beach time to ourselves, at least before the big 48-passenger Eclipse began dropping people on the beach with us. Brujo is one of the places where we don’t have to stay in a tight group with our naturalists, so everyone was soon exploring the tide pools and rock outcrops on their own, finding their own unique pictures to bring back. Personally, I spent most of my time with the Sally Lightfoot crabs, though several of us did manage to wade out to a Blue Heron without disturbing him.

The funny thing is that the animals use the beaches to play, sun bathe, or nap just like the humans.

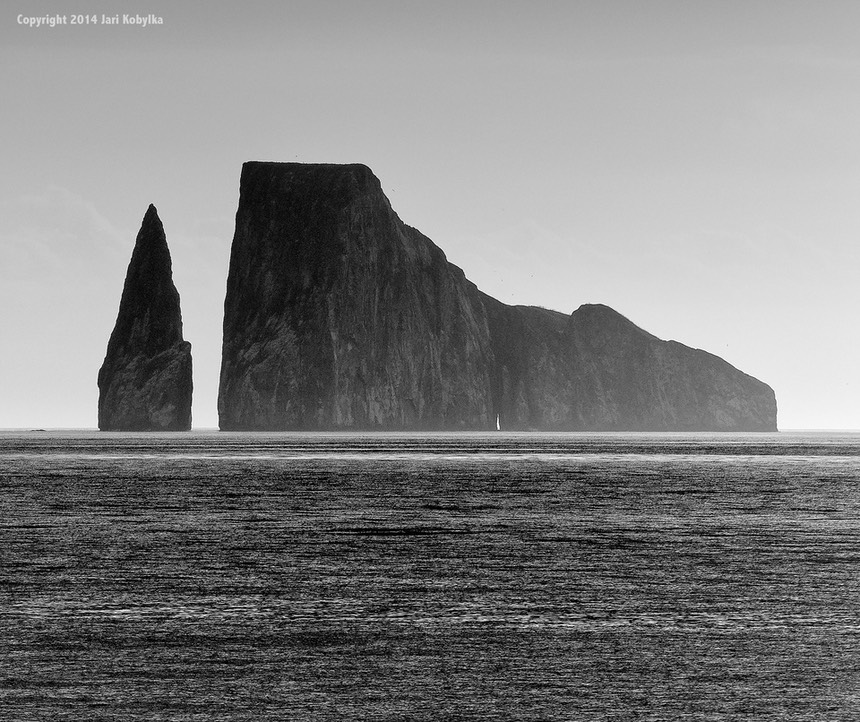

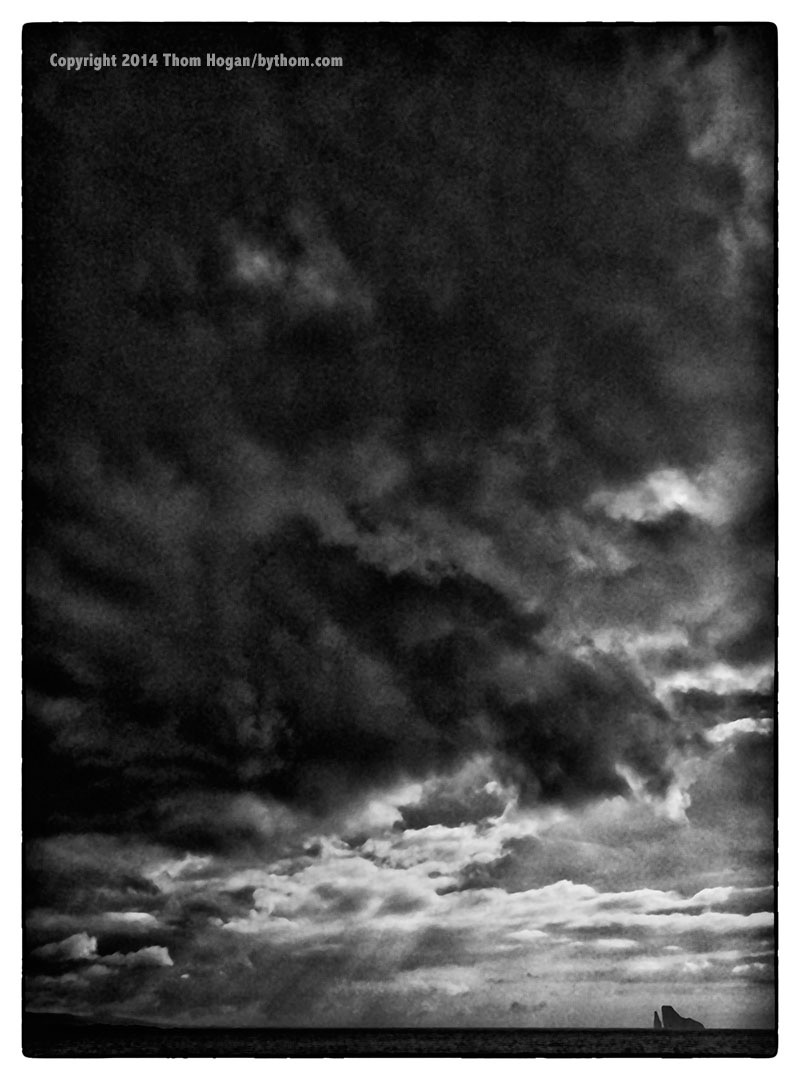

Just across from the beach is Kicker Rock, one of the Galapagos’ two geological features that everyone gravitates to. Our goal was to get out to the rock with the boat just at sunset and shoot from the top deck, a plan apparently shared by another boat, too. Fortunately, the seas were calm, the sun coming through the low clouds just about right, and we had a magical few minutes as the captain nosed the boat into the crevice that makes Kicker Rock so distinctive. While it looks like the rock split to form the narrow channel, this is actually just erosion at work. There was a softer layer of rock that, over time, has completely worn away to give us the unique split. What’s really interesting, though, is how many different takes there were on just this one distinctive landmark:

Remember when I wrote that I like “broody” shots? Well, here’s how I went with Kicker Rock with a quick bit of post processing:

Landings: Punta Pitt is a wet landing in a protected cove, generally very gentle; Cerro Brujo isn’t as protected, but is also a wet landing that tends to be very gentle.

Significant New Sightings: Maybe the heron. I can’t remember if we’ve already seen one.

Day Ten (4/8) — The Espanola Horn of Plenty

Early this morning the Letty pulled into Punta Suarez on the island of Espanola. This is the motherlode of photographic targets, and we’re attacking it with a plan. Our two sisters boats, the Eric and Flamingo I are with us this morning, and we’re the only boats here. We’ve been loosely coordinating our schedules when we’re at the same site, and this morning we literally stepped onto land the minute the park opened. The nice thing about the early start and the coordination with our other boats is that we had over an hour at Punta Suarez all to ourselves. With good early morning light, to boot.

And in that first hour, I don’t think we moved more than a 100 yards.

And in that first hour, I don’t think we moved more than a 100 yards.

Many of the male marine iguanas here are still in their Christmas colors (green and red, splashing orange). Even though mating season is over for them, a few apparently haven’t got the message to shed their colors and go back to basic black. The addition of color, of course, makes it a heck of a lot easier to photograph them. For once we’re not photographing black on black.

But this is perhaps a good time to talk about something else that should happen on a trip like this: you’ve gotten over your virginity to the place and the animals. This is a trickier subject than you might guess.

The very first time you encounter a marine iguana (or any other animal or place) you have the giddy excitement of "first discovery.” Your brain is responding to new inputs, and that’s generally a good thing. If you utilize that correctly, you can put that energy and excitement into your compositions. Most don’t, however. The temptation is to just press the darned shutter button at first encounter with a somewhat random composition. Go ahead and do that, but once that’s out of your system, you need to start using your eye/brain connection to maximize what you can do with what’s in front of you.

But we’re on what, our thousandth marine iguana this trip? The other thing sets in, too: complacency. “Oh, I’ve got a decent shot of those, I’ll look for something else.” No, no, no. You came to the Galapagos for the unique animals and environment, don’t start passing over things just because you think you’ve seen them before and have a decent shot of them. This is the thing that pros learn: there’s always a better shot, you just have to find it. Then you have to work at it. Then you have to evaluate it and work at it some more.

Now this isn’t the best marine iguana shot I’ve ever taken, not by a wide margin. But it’s a shot I took today because I was still trying to look, still trying to react to what I saw. In this particular case, it was the almost wistful look on the poor fella’s face that attracted me. That’s why I chose to crop where I did (this is within a few pixels of the full 24mp frame; in my quick post processing I took out a bit at the left where the spikes on his spine didn’t look right at the edge).

Looking at my files shows me that I got to this shot six minutes after I started shooting this fella. This is one reason why I never throw images away until after I’ve had a chance to look at them on a computer for some time; sometimes you can learn things just from the EXIF data. What was I changing? Did that work? Is there something I missed that I should have worked through some more? Your files should be full of failures. We learn best from failures, but only if we take the time to examine them and evaluate why they failed. I notice a lot of people, for example, routinely just erase missed exposures on the camera (Delete button, Delete button on the Nikons). Wait? Do you realize how many missed exposures you’ve been making? No, because you’ve erased them all and can’t count them. If I were to find that of 2000 shots I took today that 1000 of them were bad exposures, guess what I’d be working on next time I go out and shoot? Seriously, import everything into Lightroom, tag each image with your failure point, and then have Lightroom show you a summary of your failure tags.

Some suggested tags: overexposure, underexposure, missed focus, motion blur due to shutter speed, too shallow DOF, too deep DOF, tilted horizon, cut off part of subject, distracting background, distracting foreground, pokeys at edge of frame, wrong white balance, and so on.

Other early excitement came from lots of playful sea lions, mating doves, the endemic lava lizard that’s rather large, plus some additional birds, such as the Espanola-endemic Mockingbird (slightly bigger and different than its cousins we’ve been seeing).

We decided to split into “fast” and “slow” groups this morning. The “slow” group was away from the boat for over four hours. That should tell you something about our day at Suarez.

Nesting Nazca boobies on the trail. The blow-hole near the end of the trail. Female iguanas digging nests for the eggs, also on the trail. Galapagos hawks battling for territory.

But the highlight of the morning was certainly the Waved Albatross. Two weeks ago, our guide says he saw exactly one albatross. Not only did we see many of them, we saw eggs, fights, courting, taking off, landing, and lots and lots of cliff soaring. These big, elegant birds only come to land here at Punta Suarez, and they are only here the short time that they’re courting and mating. Juveniles spend their first six years over the ocean, and albatross are one of those birds that can sleep while flying. We apparently hit just as most of the birds were coming back to the island and going through their mating rituals, though at least one of them had been there awhile judging from what we found on the trail:

Punta Suarez fast turned into a focus and buffer testing site for our two groups. Even I spent a lot of time photographing the albatross and filling my buffer.

Once we were back on the boat, the captain moved the boat from the Western edge of Espanola to Gardiner Bay on the Eastern side. Our afternoon schedule is snorkeling with sea turtles, kayaking, and finally another beach combing expedition on the white sands of Gardiner.

Landings: Punta Suarez is a dry landing, though the rock dock can be wet from wave action; Gardiner is a wet landing.

Significant New Sightings: Albatross, albatross eggs, albatross mating rituals; the blow hole.

Day Eleven (4/9) — Floreana

Warning: Today’s Blog Photos are Rated R

Once again we tried to be on the islands at the first possible moment. Here at Punta Cormorant—which ironically, doesn’t have any cormorants—there’s a short trail from the panga landing spot across an isthmus to a second beach frequented by green sea turtles. Our goal was to try to catch any female who had dallied laying her eggs in the dunes of that beach. Even though we arrived early, we weren’t quite early enough. We found very fresh tracks and could see a few turtles just into the water when we arrived, so we didn’t get to see any egg laying. That’s not surprising, as most of the egg laying takes place just after midnight.

We did spend a bit of time with some dive-bombing boobies, though:

As penitence the beach did give us a pair of blue-footed boobies doing the entire mating dance. The male does a circle lifting his blue feet in a very deliberate march, lets out a whistle with his beak to the skies, and shows a little wing. The female will quack and do some beak touching, maybe do a little march of her own. At some point in this repeated ritual, the male will pretend to be uninterested and fly away, but he just circles and comes right back and repeats the dance until the female is ready. The mating, as with most birds, is something that takes all of a few seconds. So there’s a heck of a lot more foreplay than actual intercourse involved in booby mating.

We did some snorkeling at Devil’s Crown, but it was fairly uneventful. More fish I can’t name ;~).

In the afternoon we did the quick walk over to the Post Office. For over a hundred years a barrel on Floreana has served as an informal postal system. You leave off mail you want to send, and pick up any mail addressed to places you’ll be going soon and deliver it when you get there. We sorted through the sacks of mail in the barrel and easily found locations near us. There seemed to be a high concentration of coastal US, UK, and Europe, but I was surprised by some of the addresses. Maldives (the other place with giant tortoises), for instance.

We also had someone who thought that it Match.com Bay, not Post Office Bay. She left a note with her email address saying she was seeking a life partner. An interesting choice. Filters out the destitute I suppose (it takes money to get to the Galapagos, no matter how you do it).

After delivering the mail we took the pangas through the coves around Post Office Bay. The sea lions were playing. There was a shark here and there. Turtle heads bobbed around the beach. Unfortunately, we had our second equipment loss of the trip on this ride: a Coolpix AW120 was consigned to the waters after falling from a pocket out of the panga. We heard the plop. Billy dived down to try to find it, but the camera disappeared into the deep sediment on the bottom, and he couldn’t find it.

Of course, the camera has GPS, so it knows where it is. Only problem is we don’t know where it is. This is why I use a floating wrist strap on my underwater cameras. Even if the camera is heavy enough to sink with the strap, the strap tends to stick up out of the bottom where you can see it, especially since I use orange floaty straps.

The exciting spot of the ride were penguins. I don’t remember seeing them before on Floreana, but here they were, swimming around the boat.

We also had three boobies that attracted everyone’s attention. This is a good exercise in position and timing. To wit:

While everyone has a shot of the three in their files, I like Robert’s timing the best. When you have three of a thing you have three choices: (1) all the same; (2) one different; and (3) all different. I’ve seen all three variations on this gang of blue-footers, but #2 seems like the best choice in this case.

Floreana has a long, bizarre history of settlement. The story is too complicated to tell here, so if you want to learn about it, I suggest a book by one of the participants: Floreana: A Woman’s Pilgrimage to the Galapagos [Affiliate link]. Note that no one agrees on the story of what happened, though fisherman still believe that the shores of Floreana are haunted by ghosts. There’s also an out of print book and film called “When Satan Came to Eden.”

Landings: Cormorant Point is a mild wet landing, as is Post Office Bay.

Day Twelve (4/10) — Karaoke

We’re anchored back at Academy Bay on Santa Cruz this morning. The boat has some maintenance work that needs to be done in port while we’re off exploring. So it’s back up to the highlands again, this time to Cerro Mesa (Table Hill).

We found a lot of small birds, but we’re actually looking for the vermillion flycatcher, one of the few things we haven’t checked off our To See list. This led us to a long hike down a path that our naturalist thought connected back to where we started, but instead we walked a long way downhill to get to a place where the path was overgrown and would need a machete to proceed. Oops. Back up the hill we go. By the time we finally got to lunch everyone was calling it the Death Walk, much to the chagrin of the naturalists. It wasn’t really all that bad a walk, but we expended a lot of energy for no results. Okay, a few Darwin finches were photographed, but our red-bodied prey avoided us.

After a barbecue lunch, the group turned to…karaoke. The highland restaurant we dined at has a little bit of everything: soccer field, pool table, pool, hammock, you name it. But we spent an extra hour or two signing karaoke. You never know what you’re going to encounter in the Galapagos.

Most of the group seemed a bit tired after our walk and declined to participate short of me forcing them to. Personally, I channeled my inner Morrison and stuck to Doors songs, much to the chagrin of the owner, who couldn’t top my reported score of 98.5. Break on through to the other side…

Don’t worry, things will pick up in our last days, as we’re scheduled to hit a couple more of my favorite places.

New Sightings: Thom singing.

Day Thirteen (4/11) — Sombrero Chino y Bartolome

Today is less about animals than scenery, though we certainly have a few animals to shoot, too. To wit, penguins. Our early morning walk took us through some pleasant shore area on Sombrero Chino, an island whose profile is shaped like a hat, thus the name. Personally, I got caught up in photographing a Sally Lightfoot crab that was working on his molt, as did Douglas:

But if you look carefully, you can see other small things that are interesting. Well, maybe not that small. These grasshoppers are huge compared to what I’m used to in PA.

After our walk, we did a shore tour on the Zodiacs and found plenty of penguins, so after spending awhile photographing them on shore it’s back to the boat to change into swimming gear to snorkel with the little guys.

On our way to our next site, our captain pulled the boat up to one of the small nearby islands, which doesn’t have a visitation site, but does slope in a way that you can see its lagoon from the top deck. David did a quick hand-held panorama with his E-M1:

After a lunch while cruising, we arrived at one of the most photographed scenic spots in the Galapagos, the pinnacle at Bartolome. This is basically a short and steep hike from a dock up a set of steps to the top of a cinder cone. The problem, though, was could we actually get off at the dock?

Neither the naturalists nor the captain had ever seen the conditions we encountered: strong wave action coming from the North. Every other time I’ve been here the little bay we anchor in has been calm. Well, that’s not exactly true: on New Year’s Eve 1991 it was a rocking party with a ton of boats, plenty to drink, flares being fired into the air, and pangas being set on fire with people in effigy (look up the Ecuadorian New Year tradition). But the water was calm. That’s what I mean.

Today we’re seeing huge waves breaking. So huge that we can’t see the dock from the boat! That said, a few hardy souls got into the Zodiac to the dock. Apparently the actual dock area was just rolling waves, so they set off to investigate the scenic possibilities. And this is what they found:

Landings: Sombrero Chino is a wet landing in shallow water that is generally calm; for the scenic hike (there’s also a beach option that’s wet) the landing is at a dock.

New Sightings: The pinnacle.

Day 14 (4/12) — Lizards and Birds

We’re on our grand finale day, and the two islands we visit today are excellent windups to our tour.

First up is Plazas Sur, a small island off Santa Cruz. This is one of those places where you can spend all day. As you step off the dock—assuming the sea lions let you—you’ll usually find land iguanas just to the right of the trail, in the trail, and all along the both trails (to the left and up the hill). I almost immediately noted to the naturalist that it seemed like the population had exploded from the last time I was here, and the response was “the park service is considering moving some of iguanas across the channel to Plazas Norte.

The interesting thing about Plazas Sur is that the primary feed for the iguanas is the cacti, but the only cacti here generally don’t reach to the ground. Thus, there’s high competition for food, since the lizards can only reach their primary food by reaching up high (standing on something) or waiting for it to fall off. This also meant the iguanas tended to be aggressive, plus there also seemed to be a lot of mating going on.

And we saw examples of that almost immediately upon getting off the Zodiac:

But the other thing about Sur is that the terrain is great for lizard portraits shots:

One thing to look for when you have such a target rich environment is whether or not you can tell a little story. It doesn’t have to be a big story, just a sequence of shots that tell what happened. This fellow (and yes, he’s a male, probably even an alpha male), for instance, came running over to find a cactus pad on the ground that for some reason wasn’t occupied. He started chowing down. When a female came over, he shared with her. But when another male came along, he chased that poor guy off. Then he came back and mated with the female (I won’t show that image):

Not a big story. But note that because I was thinking “story” I was trying to frame up my shots as something more than lizard head. I had plenty of lens to do that, so the sequence could have lizard head, lizard head eating, lizard heads eating, lizard head hissing, lizard heads mating. Unfortunately, I was stuck in an area where the marked path was narrow, otherwise I would have done more to change angles, too. Still, I was looking for ways to make each shot different and tell a new part of the story.

Once past the lizards—which took some of us quite a long, long time, time measured in hours—you arrive at the top of the rise on the island to find a seaside cliff that the birds love flying along:

Yeah, it was crazy. For hours. I’m doing a huge amount of pruning of the good images I was sent by students here. It seems that everyone was filling buffers and cards and getting their birds in flight fill.

After lunch we moved to Seymour Norte. Guess what we find here? You guessed it, more land iguanas, more birds in flight, and a return of our favorite red balloon, the frigate bird. But what most folk got caught up shooting were the Boobie mating dances in good light, so I’ll just show a few of those.

Since this is our last shore visit, I tried to look for fitting “final” images for our trip. Here’s what I came up with:

Judging from everyone’s expressions and conversations back at the boat, everyone had a great day today, and felt the workshop ending with another of those Galapagos' big bangs. This was a long day, but one that was shoot, shoot, shoot. From iguanas at sunrise to frigate birds at sunset. I hope the images did it justice for those of you who weren’t there.

Landings: Plazas Sur has a rock dock that’s generally very easy to get off on, though it can be slippery, especially if the sea lions have also been using it; likewise, Seymour Norte also has a rock dock, though it tends to be fairly slippery and waves can come up and make it more slippery.

Day 15 (4/13) — Hurry Up and Wait Day

Today’s not really a shooting day; it’s a transfer back to the mainland day. Timing is based around the boat’s needs: they need to get us off the boat as early as possible so that they can do cleaning, maintenance, and supply replenishing, then welcome a new group aboard for the next tour.

At Puerto Moreno, everything revolves around the mid-day flight. Obviously, if we waited until the last minute to leave the boat for the flight and the next group got off the plane and through the Galapagos park service entrance procedures quickly, the boat crew would have virtually no time to do all the chores they need to do between trips.

So what happens in Puerto Moreno is this: you have an early breakfast and you’re shuffled off the boat with your carry-on luggage. Your checked luggage goes immediately to the airport. You, on the other hand, go by bus to a newly-built visitor center, which has displays about various aspects of the islands. The most interesting of which is the 3D map that shows the underwater terrain as well as the above-water terrain. It also has a tortoise pen. The expectation is that you’ll spend an hour to 90 minutes wandering the exhibits, then the bus picks you back up and drops you downtown for another on-your-own exploration.

In other words, you’re in hurry-up-and-wait mode. Generally, you have about three hours to kill before the bus comes to take you to the airport, and then you usually have another hour or more at the airport before you board the plane.

Most of us just put the cameras away and socialized. A majority spent their in-town time buying last minute souvenirs and ice cream, and again socializing. The town has a pleasant harbor-front park if all you want to do is chill. Because some of the group is immediately going on to other places from the Galapagos, such as Macchu Picchu, while the others are all on different plane flights home tomorrow, this is really the last time we’re together as a group, so we’re saying our goodbyes and reliving our favorite parts of the trip conversationally.

Personally, I’ve got a very early flight tomorrow morning to Panama so that I can make the non-stop back to Newark, so I’m winding down and thinking about what I have to do to consolidate packing tonight at the hotel.

I’ve intentionally left a few photos from the students that I haven’t shown yet on the blog so that we have something photographic left for today. So enjoy these random shots from our two weeks in the islands:

So from all of us on the Galapagos 2014 trip, a hearty goodbye and we hope you enjoyed the photos and stories we shared with you.

(Tomorrow I’ll wrap up with a discussion of camera gear used on the trip.)

Equipment Used at the Workshop

I’ve added a 2024 update to what I’d use instead of what I used on this trip to the bottom of this article.

I personally brought a Nikon D7100 kit, an Olympus E-M1 kit, and a Fujifilm X-T1 kit. I did that for a reason: these are all strong options for the Galapagos traveler that aren’t at the top pro level, and pack smallish for all the travel we do in the islands. I wanted to pit them head to head to see what each did best and which I favored (more on that in a bit). I also carried a Nikon AW1 for the water work and a Panasonic GM1 for a pocket camera.

My teaching assistant Tony also brought a D7100 kit and an X-T1 kit plus a Nikon AW1. Amongst the students there were mostly Nikon DSLRs (mostly D7100’s, but a D300 and D700 amongst them), plus several Olympus E-M1s. A few people carried GoPro, Coolpix waterproof, or Olympus Tough cameras for water work, but there were at least six Nikon AW1’s total on the trip out of the 18 of us carrying cameras.